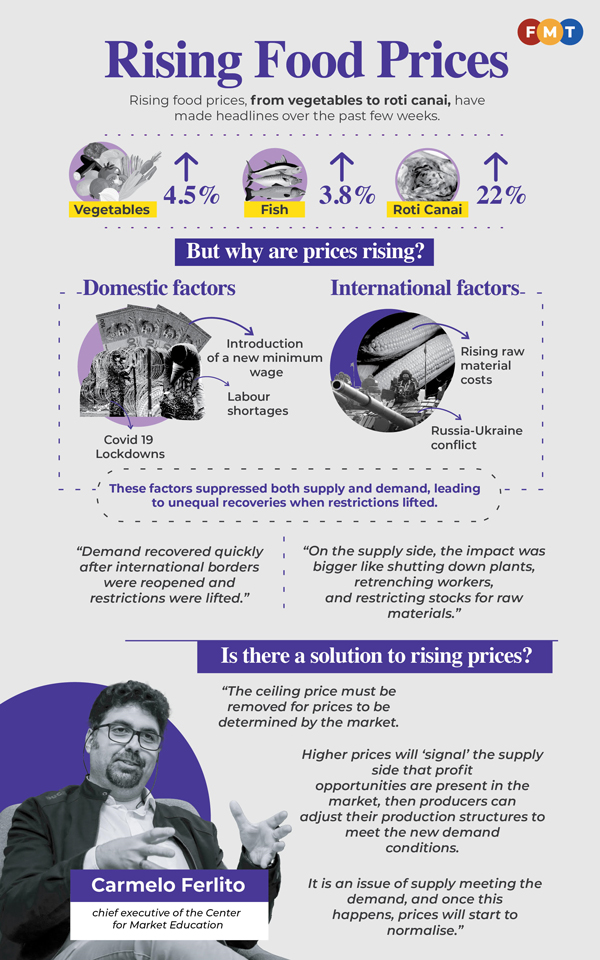

PETALING JAYA: For the past few weeks, the rising prices of food, from vegetables to roti canai, have made headlines, prompting the government to institute measures including prolonging ceiling prices and export bans.

But why are prices rising and will the government’s measures actually work? FMT takes a closer look at the rising prices of food and the way forward.

Why are prices rising?

Center for Market Education chief executive Carmelo Ferlito said the rising prices of goods are due to domestic and international supply chain issues, including the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict as well as a spike in the cost of raw materials.

On the domestic front, he said, lockdowns implemented to curb the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, labour shortages and the introduction of a new minimum wage were also factors.

In recent weeks, there have been reports that the prices of vegetables and fish have increased 4.5% and 3.8%, respectively, while restaurant owners have said that roti canai could cost RM2.20, owing to higher prices of wheat, dhal (lentils) and cooking oil.

In the case of chicken, the retail price was capped at RM8.90 per kg, which farmers say is too low. The government has announced a new ceiling price of RM9.40 per kg effective today.

Ferlito said the lockdowns led to a reduction in both supply and demand, and while demand recovered quickly after international borders were reopened and restrictions lifted, this was not the case for supply.

“On the supply side, the impact was bigger – like shutting down plants, retrenching workers, and restricting stocks for raw materials. This discrepancy between supply and demand has led to an increase in prices,” he said.

As for chicken prices, he said the cost of raw materials, particularly chicken feed components like corn, had also risen. “Feed represents up to 75% of the running costs for a poultry farm,” he said.

The price of grain corn and soybean meals – used to make chicken feed – increased by 13% and 11% in April, while feed prices in some cases reportedly reached RM1,900 per tonne, up from RM500 per tonne.

Pricier chicken on the horizon?

Ferlito said for prices to come down, specifically in the context of chicken, the ceiling price must be removed so that it can be determined by the market.

“Higher prices will send a ‘signal’ to the supply side that opportunities for profits are present in the market, and then producers can adjust their production structures to meet the new demand conditions,” he said, adding this was not necessarily a bad thing.

“When this process, which takes time, is completed, price tensions will cool down.”

As for other food items, he said, it is an issue of supply meeting the demand, and once this happens, prices will start to normalise.

What can the government do?

Ferlito said on top of letting market forces determine prices, the government could issue food vouchers to those in the bottom 40 (B40) to spend on food items.

This subsidy should not last longer than three months, by which time the market would have corrected any price tensions.

“This would be better than cash aid, as it would better ensure that subsidies are actually spent on food items,” he said.